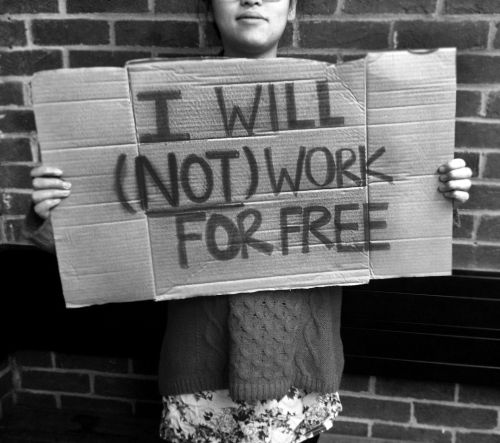

Unpaid work is one of the current buzzwords across the dance industry: we all want to talk about it and decry it, however these conversations lack a basic understanding of the role of unpaid work within our industry, how it is perpetuated, and under which circumstances it is acceptable. In an industry which has been forcibly shifted towards freelancing, how many of us can tell our landlord "I can't pay my rent, but check out this solo I'm working on"?

Unpaid work is one of the current buzzwords across the dance industry: we all want to talk about it and decry it, however these conversations lack a basic understanding of the role of unpaid work within our industry, how it is perpetuated, and under which circumstances it is acceptable. In an industry which has been forcibly shifted towards freelancing, how many of us can tell our landlord "I can't pay my rent, but check out this solo I'm working on"?

Between the end of 2012 and mid-2013, I conducted a number of interviews with people across the dance industry - from students and new graduates to midscale choreographers and artistic directors - about the issue of unpaid work within our industry. Around then, Dance UK had published an article containing statistics about paid and unpaid work in our industry, but I felt that further research was needed into the fine details of unpaid work, how it sustains our industry and impacts on its members. Only once we can put unpaid work within its wider context can we start to understand its function within the industry and how to place checks on it.

That was two years ago, however as part of my work through Cloud Dance Festival and my own independent work, I continue to interview dance artists and research regional dance ecologies and artist support provisions, providing me with an ongoing perspective of how our industry treats the people within it, the career progressions available to them, and to what extent unpaid work plays an integral role.

Actually, the fervent debate isn't about unpaid work in general, but specifically about unpaid dancers. This in itself is divisive, as it deliberately ignores all the people working across the industry in other roles who are also not being paid or being paid fairly, and also ignores the diversification of our work with portfolio careers: how many of us are just dancers, and not teachers, choreographers, producers, writers, photographers, video producers and/or designers as well? No matter which capacity we work in, we are still entitled to a fair wage, even if our role is ancillary rather than performing.

It is reductive to focus too narrowly on unpaid dancers, as not only does this write off everyone else in the industry, but it also implies that it's okay if people are paid something, no matter how little it is. It is not. Low paid work is just as harmful, and perpetuates a culture in which industry professionals do not have to be paid what they are worth, and they should be grateful for the pittance which they do receive.

Where We Are Now

At its core, this situation is about people not having money, and choosing to create work without any, or without sufficient financial support. The problem stems from dance not being simply a day job but a vocation, with people driven to create, dance, perform or do other dance-related work regardless of whether there is any money in it or not.

As the industry doesn't have enough money itself to support the ever-growing number of dance artists in it, this means only a proportion of the industry is ever going to receive financial support, even while available sources of funding continue to dwindle. As we know, dance is an extremely expensive artform, considering the eye-watering cost of creating new work and the even more alarming cost of touring said work.

Yet people will create work for free regardless, to try out a new idea or for the opportunity to have their work shown and hopefully taken forward: a case in point is Resolution!, a celebration of a very large unpaid proportion of 84 choreographers risking putting themselves into debt over the chance to have their work performed at The Place. This is not to single out The Place, however; the majority of unpaid platforms are venue-led, which means their costs don't include hiring themselves, and therefore are minimal. At which point does opportunity become exploitation?

Considering that the minimum cost of creating a new small-scale work is around £1000, unpaid platforms mean that the choreographers are stuck with trying to find the money for studio space, costumes and other sundries, while the choreographer, dancers and some or all of the other collaborators go unpaid. Because of the constraints of trying to create new work under such circumstances, the choreographers rarely have the chance to create work representative of their abilities, which reflects poorly on them and their dancers, and ends up being indicative only of what they can create in a tiny number of rehearsals with half their dancers missing. Yes, I also put on unpaid platforms, and I really don't like asking people to perform or work for free, which is why I don't do it more often - and when I do, I try to make it worth their while.

It is accepted that new graduates - and less new graduates - are required to undertake a certain amount of unpaid work in order to secure the professional experience necessary for applying for paid work. Yet this logic is flawed: by the time dancers complete their vocational training, they are of a professional standard and therefore eligible to be paid. With fewer and fewer company or apprenticeship jobs available for new graduates, they are being forced into the freelance life without having been equipped for it by their training, yet this is the time when they need the most support to continue their ongoing training through regular class and work opportunities, theoretically with the latter funding the former - though that too rarely happens - while they begin to establish themselves within their artistic community.

People are also generally keen to support each other to help make things happen, but the system breaks down when what is a favour becomes expected or even demanded, and the people who are giving up their time are treated poorly by the person or friend who they are helping. While treating one's collaborators poorly is never acceptable, it is even more unacceptable when people are making personal and financial sacrifices to help others, and yet this behaviour persists. Even in a milder form, many people feel that they are not appreciated or respected for the work they are doing for free; appreciation, respect and gratitude don't cost anything, so they shouldn't be in such short supply.

People should never be made to feel grateful that someone is offering them unpaid work, while loyalty is in too-short supply: if Person A gives up their time for free to work hard for Person B, then it's very likely they'll be upset if Person B then gets Persons C, D and E to work for them too, not valuing A's effort or even consulting them. Even worse - as we probably all know - is when companies continue to work with the same body of dancers on unpaid projects, but as soon as they receive funding, they choose different dancers instead, not giving priority to the dancers they've worked with over a long period of time. This industry is about the relationships we build with each other, and it's a very small industry, so treating people fairly and with consideration is all the more crucial.

It would help if we had a strong advocacy body and a strong union to represent all members of the dance community, but we don't have either. When you appraise the impact of unions such as the Musicians' Union, it's hard to justify the failings of Equity - especially after being informed of an incident which took place a few weeks ago where a choreographer was working on a commercial project with a tiny budget which could only cover the choreographer but not the dancer. Equity became involved and demanded that the fee was stripped from the choreographer and given to the dancer instead. So, thanks to Equity's involvement, the dancer was paid but the choreographer had to work for free. When did Equity stop representing choreographers?

The Big Scary World of Funding

As we know, it's always a cause for celebration when one of our friends or someone we know receives Arts Council (ACE) funding, however we never usually learn exactly how little they've actually received, compared with the actual cost of creating their project. Because people always feel under pressure to reduce their budgets by as much as possible to increase their chances of funding, too often the funded projects receive too little money to carry out the project successfully, and corners have to be cut, and therefore artists' fees. For all of Arts Council's insistence on people being paid fairly, this is still not happening, as we all know all too well.

Of course, it's not just down to people trying to squeeze a budget into something a few dress sizes smaller in order to get funded: some people are genuinely crap at budgeting, and that's a different matter, as are people who try to overdo the in-kind support part of their applications by underpaying everyone.

Because most dance artists do not receive admin and producer training as part of their vocational training, it's understandable that a significant number of them are terrified of funding applications and don't understand how to fill them out. This means that an unnecessary number of funding applications are rejected because the people applying don't understand how to answer the questions - but they can't afford a producer to do it for them, or they've picked an inexperienced producer who doesn't know how to answer the questions either.

Knowing how to find other sources of funding would help dance artists too, however these are of course drying up, or being reallocated, for example IdeasTap's Innovators' Fund which has funded many small-scale dance projects including the initial creation of John Ross's Wolfpack.

Crowdfunding has swiftly turned into an industry bugbear: buoyed by the early crowdfunding successes, people are becoming overreliant on it as a source of extra cash, which is in turn burning out all their friends, peers and family, but as it doesn't represent guaranteed fixed income, this means that projects dependent on crowdfunding are likely to result in artists being paid less than expected or not at all. Ditto for projects which are "paid subject to funding".

Far too many people believe that Arts Council's Grants for the Arts (GFA) funding isn't accessible, which is a fallacy; since the transition to NPO-funded organisations in 2012, with NPO-funded organisations no longer allowed to apply for GFA funding for adhoc projects, the majority of grants and indeed funds within dance have been awarded to emerging and small-scale artists. As an example, although we are only three-quarters of the way through the current financial year, over 75% of grants and 56% of funds have been awarded to small-scale artists. Apparently the current acceptance rate is around 50%, which means ACE must be inundated with grant applications from emerging artists, but the figures show that ACE is clearly prioritising investment in the emerging sector of the industry rather than, say, the independent midcareer artists, who only receive on average around 15% of awarded grants.

And this is what is fundamentally wrong with our industry. I hope we all know the vital importance of the independent midcareer / midscale artists within our industry: not only do they represent the support, investment, experience and learning which helped them get to where they are, but they are also the artists who the younger artists look up to and learn from, and most crucially, they are the ones who continue to take risks: the younger artists daren't, in case it prevents them from getting funding, and the large-scale artists stopped taking risks long ago. Look at Ben Duke's Like Rabbits: a wonderfully whimsical and unconvential duet with a madcap "trailer" at the end; the show feels more like a personal project than a company work. (Like Rabbits received ACE funding nearly two months after its performances at The Place.)

The problem with creating midscale work, however, is that it costs a hell of a lot more than, say, a one-week R&D. It is becoming harder and harder for independent midcareer artists to secure the funding to create new work, which means that at this critical time in their careers, they are having to wait perhaps two years at a time to receive the funding they need, with numerous rejects and setbacks in the interim, which starves the rest of the industry of their input and presence. If they're not creating new work, then they disappear from our radars, and that shouldn't be allowed to happen.

Are you wondering where I'm going with this? The point is that independent midcareer artists hire younger dancers for relatively lengthy projects. Younger dancers then hire other dancers to work for them. And so on. So although funding a midscale project may be seen as a significant investment for ACE, it also represents significant investment across the industry resulting in the creation of numerous and paid jobs. And numerous and paid jobs are exactly what we need, so why is ACE not supporting this?

And another question is why ACE is not supporting artist support programmes through the dance agencies in the North West: MDI in Liverpool and Dance Manchester. Artist support programmes are essential for nurturing and developing both artists and audiences, through offering space, residencies, class and commissions as well as programming dance which is important for local artists as well as local audiences. Artist support programmes are also vital for providing in-kind support which is needed for securing further public funding. Yes, artist support programmes cost money and the return is qualifiable rather than quantifiable, and may be perceived as a luxury, but without artist support programmes in place - for example those at Dance City, Swindon Dance, Dance Base and The Place - artists are not being supported in the creation of new work and securing funding which will enable them to hire and pay dancers. And strategic dance agencies being told by ACE to halt all artist support makes no sense at all.

What All This Means

There are many impacts of unpaid and low paid work. How people are treated despite giving up their time to do others a favour is one example, as is the resulting standard of work from creating work for free; I don't need to mention these again.

Overwhelmingly, if artists are not treated professionally - i.e. are paid for their work and treated accordingly - then they are not able to think of themselves as professionals, and the rotting core of this industry is amateurism, which is what we get when people don't think, act, are paid or treated as professionals. It affects how they treat others, what they expect from others and what they create, which makes it an insidious widespread national issue. Even the project-funding model is partly to blame: when artists are too intimidated to ask for the amount of money they actually need for their project, the resulting work will not be of full professional standard, despite ACE's best intentions.

And of course, when funds are limited and people are resorting to working for little or no money, then artists are unable to develop and grow, which is what they have to do to sustain themselves and propel themselves forward in this industry. They need the funds to continue taking class regularly and watching other shows, otherwise they will not be of a standard to secure more paid work and develop their careers further. Without that, we end up with stagnation, which is what we currently have.

These constraints have thankfully resulted in several artist-led support programmes in response to artists' needs: Martin Hylton's Gateway Studio Project in Gateshead; TripSpace in London, tailored to artists' needs for affordable space, class and workshops; the Gracefool Collective in Leeds, who tonight celebrated the launch of their tri-weekly professional class, funded by the Arts Council, and Kitty Fedorec's Technique Exchange classes at Chisenhale Dance Space, aimed to fit around freelancers' erratic schedules and need for affordable class within a supportive community.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, however, many artists are conscious of how the large organisations are themselves perpetrating this expectation of dance artists working for free - whether through offering unpaid platforms or unpaid roles - and many of the artists I interviewed were angry that these organisations are receiving significant amounts of funding but are not willing to do better. If the large support organisations cannot locate and/or prioritise funds for artists and for the people they hire to work for them, then who will? And how can they justify working in this way? - especially considering how damn small this industry is. Small, and so very exploitative. And so very very very small.

Where Do We Go From Here?

What we're seeing is that being an emerging artist is not sustainable - and that's without taking London's insane living costs into consideration. People on the continent are amazed that emerging dance artists in this country are not able to support themselves through working in dance, but that's what we get with both an economy and government hostile towards the arts industry and those who dwell in it.

But it's still worth it, however hard and depressing and difficult it gets. We have people everywhere who are doing what they can to make things better for us in their own way, and we should never lose sight of that or stop appreciating and valuing their work.

Gary Clarke is a good example: pretty much everyone I spoke to said that regardless of their stance on unpaid work, they would or they have already worked for free for the opportunity to work with him. Better still, a duet he created in his living room for free ended up being performed at the Royal Opera House's Linbury Studio Theatre by Tom Roden and Pete Shenton of New Art Club as part of a nationwide tour. So sometimes, it's worth it.

It's ignorant and short-sighted to demand that people stop working for free altogether. Not only would work not get developed and created, and this industry would effectively grind to a halt, but also it's important to sometimes give back to the industry, which is something this industry is good at doing: we're ultimately a large dysfunctional family, so we support our own.

But what we need is a shift in attitude: in how we treat each other and most importantly in how we pay each other, and not feel we can get away with paying other people rock bottom because we can probably get away with it.

It's important to support each other and to give as well as take, if you're the one doing the taking. It's also so so important to show more appreciation for people working for each other for free, and to acknowledge and respect the sacrifices that people are making to help others. We need to change how we make work, treat each other and make changes happen: it is so vitally important for dance artists to speak out and not remain passively accepting of this situation. The more people who speak out and join forces, the better the chance we have of effecting change.

It's also important to pay people properly, and to not accept the cop-outs that are Equity rates, as they should only be applied to new graduates and possibly not even then, as they don't represent a decent wage considering the skill level of the dance artist. Don't compromise on costs, especially not when it comes to paying others.

If it's within your control, pay people on time. It's bad enough to pay people poorly without making them wait for months on end to be paid. Sometimes there are extenuating circumstances, which is valid - as this is the arts and things never go smoothly, do they? - in which case pay people when the funds come through, but as I've learned (from being on both sides), no amount of nagging or chasing will speed things up much, but at least it destroys a number of professional relationships along the way... which is just ignorant and stupid.

Choose your projects carefully. Some projects are good to have on your CV; others are not. Some projects are worth working on for free, because of the experience you will get out of doing it, what it may lead to or the people you will get to work with as a result. Those are the unpaid and/or low-paid projects worth working on. We also have to remember that not every idea has to become a new work, nor does every new work need to be created. It's better to focus our energies on the projects which matter, especially for the freelancers among us who have to work on multiple jobs at any time just to break even.

Use your funds wisely. This applies to large organisations as well as new and emerging choreographers, however the big players really do need to change their game regarding how they pay - or don't pay - dance artists. If you're a perpetrator of unpaid work, think about how you can do things differently, and then act on that. There is no allowable justification for the exploitation of dance artists or dance industry professionals.

And finally, don't abuse each other. Unless you're Article19, of course.

This article is in response to an unpaid commission by Dance UK for an article on unpaid dancers; a tailored version of this article will appear in their next magazine.