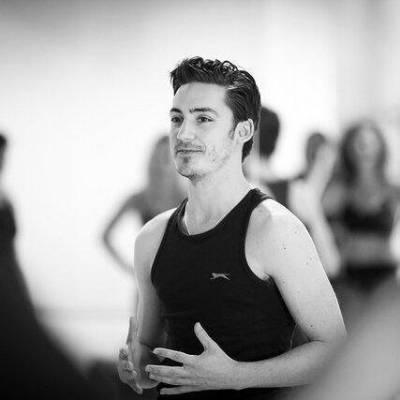

Drew McOnie is the artistic director of the recently-launched McOnie Company, and choreographer/director of the new ‘theatre dance’ show, Drunk. Drunk is seventy-five minutes of alcohol-themed, high-energy song and dance, performed by an impressive eight-strong cast of dancer-singers and an excellent live band. It left me very entertained, but triggered many thoughts and questions about what it is that we do as dancers/choreographers and who we do it for. To unpack some of these thoughts, I sat down with Drew to hear a little more about the ideas behind Drunk. In this two-part conversation we pondered everything from bridging gaps within the industry and the importance of process, to accessibility and the role of stereotypes.

Elise Nuding: I’m curious to hear more about what you are trying to do in terms of bridging genres. Previously, you have talked about a gap between a ‘pure dance audience’ and a ‘pure theatre audience’; I’d like to hear a little more about what you mean by those terms.

Drew McOnie: Well, it’s funny– the reason I feel that there is a bridge to be made is more because of my experiences as a dancer than as a choreographer. As a dancer I was trained classically, in musical theatre, and in contemporary– but really as a ballet dancer first and foremost; it was never my intention to become a contemporary dancer. But, working in both the musical theatre and contemporary fields, I’ve been fascinated by the belief systems of each towards the other. Because I just love dancing, I love dancers, wherever they come from, whatever dance they like to do– I think dancers are special creatures. But the interesting thing to me is that often they don’t seem to support each other, thinking the other is not doing the cool thing. Contemporary dancers often think that the West End is all jazz hands and high kicks, and musical theatre dancers seem to think that contemporary dancers spend all their time just ‘finding their bodies in space.’ But I think there are inspiring things in both approaches, and that each field has a lot to learn from the other.

And then, when I started to take my work as a choreographer to different platforms in the contemporary world, I found some of the responses I got to some of my work fascinating– it was often one of complete confusion. When I very first did Resolution! I was in a triple bill with two other pieces. They were both amazing, but they could not be further away from what I was doing; I turned up at The Place with a Judy Garland piece, where the girls wore sequins on their dresses and were shimmying in time with the music. It was unashamedly theatrical. But what was interesting was that, in taking something that was quite accessible and normal in theatre terms to somewhere like The Place, it ended up becoming more avantgarde than it was intended to be. The stark difference between my work and the other two works in the bill completely divided the auditorium about what was expected, and about what was cool and not cool. And that really shocked me.

EN: And the thing is, when we say ‘contemporary dance’, that can mean so many things. The spectrum is huge!

DM: Yeah, it is a loose term, isn’t it?

EN: Which is actually a positive thing, I think, because there are not so many boundaries delimiting what ‘contemporary dance’ can or cannot be…

DM: Yes, I like the looseness. And, actually, that’s an interesting point, which I hadn’t thought about before, in that contemporary means ‘of now’, and I feel like a lot of contemporary choreographers’ sole focus is on trying to do something that’s new, or trying to break something down. But there’s not a lot left that can be new or shocking in dance: everyone’s done it all. So I think that some of the distaste comes from the fact that contemporary dancers/choreographers sometimes think that what musical theatre choreographers are doing is just recreating what’s already gone before, and there are a lot of cases where that is true. I do that sometimes! But I think that musical theatre choreographers are not obsessed with this notion of being new, and I think that’s where some of the miscommunication happens.

EN: Yeah, I know what you mean. But, equally, I think you could say that there are a lot of contemporary choreographers who are just recycling movement from other choreographers, or eras– which is not necessarily a bad thing! But yes, there is a certain value placed on being innovative, on having an individual choreographic style.

DM: I think that one difference is that, in musical theatre, people are happy to pass the torch on. Most of the support I’ve had has been from people involved in the musical theatre sector who feel there is a craft to the art that should be continued, should be handed down. Whereas in the contemporary sector many responses have been along the lines of, ‘Well, what have you got for us? But that’s not new, that’s not different’… At the moment I am really passionate about introducing a contemporary dance audience to theatre dance, and to the skill involved in it, and the other way around. A lot of people who are more of a theatre audience have come to see Drunk have said ‘I didn’t realise that was dance!’

EN: So, when you use the term ‘pure dance’, you are more or less referring to contemporary dance?

DM: Yes, although I suppose another way of putting it would be to say work where dance is the foreground. When you go to see a dance company you go to watch people dance, whereas very often in musical theatre you go to watch a story, or listen to the songs, and dance happens to be part of that structure.

EN: I am curious to hear more about the process of ‘Drunk’– do you see bridges between the two fields in terms of how the work came together, not just in the outcome?

DM: I think that the way in which we operate more like a dance company, and where Drunk is maybe more like a piece of pure dance, is in the way it was made. The creation of material was very process-driven, with a lot of the material coming from the dancers themselves. And this is something that the dancers have really latched onto, and loved, because it’s something that they do not get to do very often. There is definitely a notion in musical theatre that the choreography is already made up before you come into the room. The notion of playing games and setting tasks (which of course is very common in contemporary dance) is unusual. The fact that these games/tasks were, in Drunk, instigated by narrative is perhaps what situates it more on the theatre end of the spectrum.

EN: This is really interesting. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the process/product divide– or the lack thereof. However, the audience only ever sees the product, which is something that always seems a bit of a conundrum to me– it is only one tiny slice of a much larger process than often gets taken as representative of the whole, even though it may not be.

DM: Yes, and the musical theatre industry is definitely very product driven!

EN: Of course, there are many contemporary choreographers who concern themselves with making the process visible, making it part of the product. And there is currently a lot of emphasis in the contemporary scene on opening up the creative process– it is often part of the drive towards education and outreach. But, I would posit that perhaps sometimes the outreach element is the only reason for this emphasis, and some choreographers would not otherwise be interested in opening up their process. How do you feel about this? Is sharing the process important to you at all?

DM: What is important to me is the outcome of the process, which is the product, but it is also a greater understanding and greater commitment on the part of the performer. For me, Drunk has been completely overwhelming, in many ways, but part of that has been the way that the dancers have invested in it, the way that they feel so proud of it. For our first performance, in Leicester, we had a standing ovation of about 300 people and the looks on the dancers’ faces were just incredible for me to see. The sense of ownership that they had– that they had made it, that it had come from their souls– was very moving. And that’s where process comes in. Even though the audience will never know what the process was, it is there in the show, in the dancers’ commitment.

EN: This is interesting with regard to the debate about the commonly-seen credit in contemporary dance of ‘choreography created in collaboration with the dancers.’ The debate tends to focus on intellectual property rights, the academic ownership of the work, or on a concern with over-crediting the choreographer. Of course, it is important to give credit where credit is due, but perhaps it’s not really, or not only, on paper that ownership matters; it matters in the performance of the work…

DM: Indeed, and the thing is, if this show does what we’re hoping and there is a future production, it will be an absolute nightmare to recast, because the dancers were so involved in its creation.

EN: Welcome to contemporary dance!

DM: Exactly, and there’s such a skill in that restaging. And actually– as a company, as a company director, as a crazy person– my obsession is with the performer, not the performance. It always has been, and the McOnie Company was set up to celebrate the dancer– this is why, for example, we include their individual twitter handles in the program. In musical theatre it is very unusual to have a cast announcement for a group of dancers, because people are usually not interested. It’s little things like putting the dancers names on the back of the flyer– the marketing advice you get about that is ‘it’s not necessary, they’re not household names’. My response is ‘yet!’ The point is that if no one starts to celebrate the dancers in their company, they will never be celebrated. Gone are the times when there were celebrity dancers, known outside of the dance sector…

I mean, this is our first undertaking under the company banner (other stuff I’ve made and presented was done independently), and I’ve been overwhelmed by the response we’ve had– basically by the support. We’ve had a lot of support from the musical theatre sector because they feel like it is for them, by them, and with them. So it will be interesting to see what the response is from the more dance-based sector because they’ve already got what we’ve got to offer, in a way. What they don’t have is the singing side of things– whether people will be open to that we’ll have to see.

Part Two of this interview to follow next week... Stay tuned!